I love the smell of horse manure in the morning. It smells like… a victory levy and campaign.

Butchered quotes aside, the levy and campaign system gives you a chance to explore the ins and outs of feudal warfare, where waging successful campaigns was as much about convincing your various vassals to join your efforts as it was in actually winning the battles themselves. Far from a dull affair, the levy and campaign system introduced in 2021’s Nevsky: Teutons and Rus in Collision 1240-1242 puts people behind the counters, with lords who care about victory, making strategy as much about who you can convince to take the field as about dice rolls and combat charts.

Also, you can storm castles. Who doesn’t love that?

Introduction to the Levy and Campaign System

Volko Ruhnke, otherwise known for GMT’s COIN series, begins Nevsky by recognizing the human war machine’s greatest foe isn’t artillery, fleets, or public will, but that most fickle of nemeses: weather. Slogging one’s soldiers through mud, or across ice only to see your retreat turned to water, is a dance Nevsky demands you to learn, then complicates it with greedy lords who’d rather take your coin and cattle for nothing than risk their hides in battle.

If seeing a calendar as one’s nemesis doesn’t sound like the most thrilling thing, consider it instead as a shifting battlefield. Getting lords less willing to commit to a long campaign on the move in seasons of easy travel is important, as is ensuring your larger armies have the food to press deep into winter and secure towns and castles. The profit therein might persuade those dubious lords to keep their swords with you, or else disappear back to their farms.

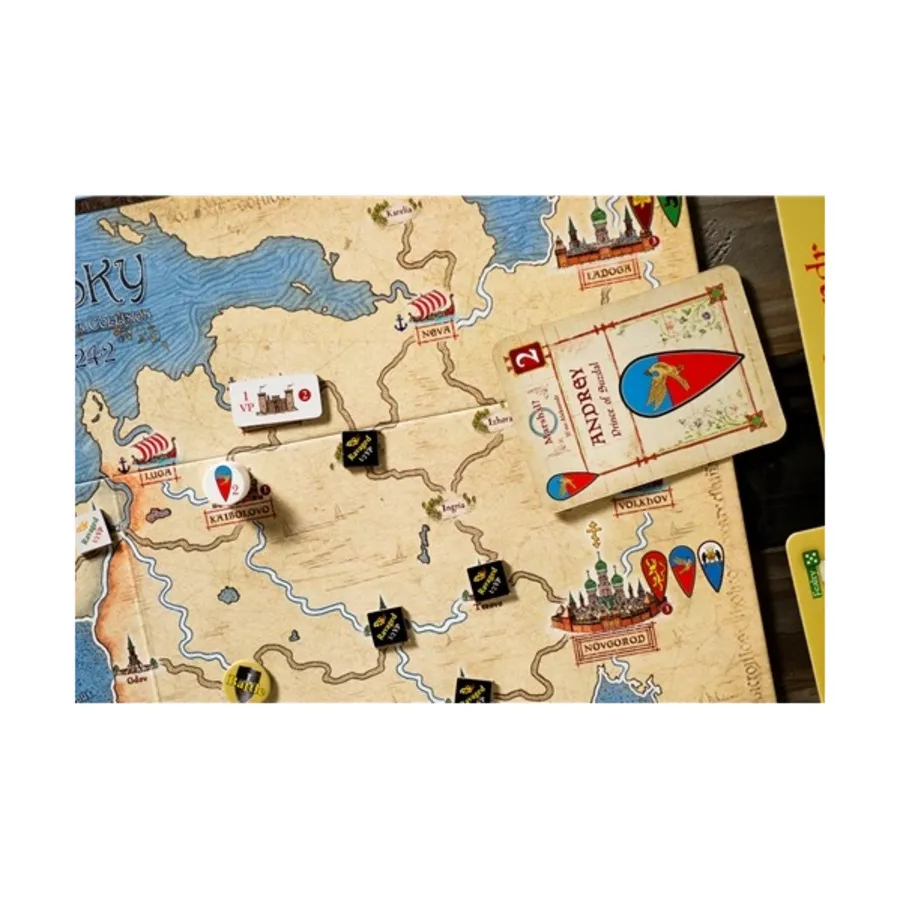

Playing Nevsky feels, at first, like dealing with spoiled children. Everyone wants their cut, and they’ll only help you at their whim. Half the fun is wrangling these disparate elements into place, using slim resources, raids, and feints to get forces where they belong on the beautiful, non-hex grid map. You’ll plan for this during the game’s Levy phase, wherein, much like the COIN series and other CDGs, a hand of cards will give you options to play each for an event or for points to use for crucial necessities like sleds, boats, and upgrades. This is also where you’ll decide how far into Rus territory you’ll be tossing Lord Fancypants, or whether your fur-clad farmers will have enough food to hold Izborsk against the invaders.

this during the game’s Levy phase, wherein, much like the COIN series and other CDGs, a hand of cards will give you options to play each for an event or for points to use for crucial necessities like sleds, boats, and upgrades. This is also where you’ll decide how far into Rus territory you’ll be tossing Lord Fancypants, or whether your fur-clad farmers will have enough food to hold Izborsk against the invaders.

Making these choices is the meat of the game, a rash of back-and-forth bluffing and hopes soon put to test by the Campaign phase, where all your dreams get destroyed by brutal reality. First, you’ll plan all your intended actions at once by creating an action deck, after which you’ll alternate taking those actions. As they play out, you’ll run into miscalculations, like stranding poor Lord Fancypants at a river’s end with impassable muddy paths to get him supplies. Or perhaps you’ll attempt to wage haphazard medieval combat, but the dice don’t go your way, either through lack of preparation or sufficient real-life sacrifices to bring Fate to your side. Regardless, success feels like a real achievement rather than a foregone conclusion.

Now your battered armies and lords must be convinced to continue the fight, or, if left on the brink of starvation with but a single sword to their name, to leave it.

And that’s just the first round.

In Nevsky, the invading Teutons and defending Rus are asymmetric, with wide strategies on both sides. The Teutons start under immediate pressure in most scenarios, with Rus gaining victory points through their starting cities. Aggression is important, but overstretching can leave your wandering, murderous  knights vulnerable to counters from the pesky bushes. And if all your lords on the board give up the ghost, the game’s over. Meanwhile, Rus has to choose where to commit, when it’s worth forcing a siege, and whether a tantalizing sneak attack into Teuton territory is too much fun to ignore. Of course, to do any of that, your lords have to love you (and your money).

knights vulnerable to counters from the pesky bushes. And if all your lords on the board give up the ghost, the game’s over. Meanwhile, Rus has to choose where to commit, when it’s worth forcing a siege, and whether a tantalizing sneak attack into Teuton territory is too much fun to ignore. Of course, to do any of that, your lords have to love you (and your money).

What makes Nevsky and the Levy-and-Campaign system both brutal and beautiful is the marriage of resources, politics, and war. Your forces aren’t magically funded, they don’t march forever, and supply lines aren’t just an abstraction to a board edge. The solo mode isn’t an abstraction either, with specific setups to ensure you’re not just playing both sides, trying to forget your strategy every time you swap spots.

In short, the Levy and Campaign system is operational-level war gaming in a rarely visited feudal era, and it’s most definitely worth your time.

More Levy, More Campaign

Should you find your lust for feudal delights isn’t sated by a single title immersed in Eastern Europe, then fear not, because Ruhnke has ported the system into both Spain and Tuscany. Grab a bottle of red and settle in, for there’s warfare to be done.

Almovravid: Reconquista and Riposte in Spain 1085-1086 brings politics and provisioning to Hispania, shrinking the space and increasing the sieges. The same calendar-driven traps remain, with flighty lords liable to leave your desire for death unmet should you be stingy with your bribes or moronic with your movements. The two sides here—Christian and Muslim factions—bring heavier asymmetry to the table, necessitating more divergent tactics than Nevsky. I’d suggest upping the tension even more by using the included screens to hide the forces in play, making every move a potential ambush.

movements. The two sides here—Christian and Muslim factions—bring heavier asymmetry to the table, necessitating more divergent tactics than Nevsky. I’d suggest upping the tension even more by using the included screens to hide the forces in play, making every move a potential ambush.

Inferno: Guelphs and Ghibellines Vie For Tuscany, 1259-1261 visits Italy with veteran designer Enrico Acerbi pitching in expertise. Among a number of new unit types, Inferno’s big addition is treachery, which is a word that always makes a game more interesting (seriously, I struggle to think of a title where treachery doesn’t add some zest). Like in Almovavid, the terrain—you’re playing amid Rome’s infrastructure—eases up the supply burden, putting greater emphasis on combat and travel.

So, naturally, with more roads there’s going to be more rebels. They combine with treachery cards to give you new and dastardly ways to turn regions to your favor and give your opponent fits. Who needs a costly siege when you can convince a stronghold to throw up your flag with a little coin in the right pocket?

While Nevsky holds strong as the most recommended game for Levy and Campaign newbies, it’s a tough choice between Almovavid or Inferno for which to try next. I suggest looking at the label on the wine you opened when this section began and let that guide you.

Logistics Wargames on the Lighter Side

Okay, so you’re intrigued by Nevsky, by getting all your precious resources in the right places to wage successful war, but a glance at those rules makes you a tad uneasy. Or maybe you’re looking for a logistics-friendly experience for your next big game night, and a title for two just won’t cut it. If you’re jonesing for some planning action, here are a couple games that fit the bill:

The Quartermaster General series (Ian Brody), picking the conflict you like the most, offers a blazing fast version of various wars in which you, guiding a country, burn through a unique deck to claim territory and accumulate victory points. Logistics are front and center, as all of your precious units must remain in supply at the end of your turn or poof, they’re gone. Turns, even with five and six player games, zip by as you’re generally only playing and drawing a single card. You’re also never bored, as events ensure units can pop up just about anywhere.

What’s more, after a couple games, your group will likely be fast enough to play a round of this in an hour or 90 minutes, making it an easy run-back.  Expansions, particularly for the WW2 version, add a-historical openings and strategic depth while bumping playtime by only a few minutes. This is a classic series for a reason.

Expansions, particularly for the WW2 version, add a-historical openings and strategic depth while bumping playtime by only a few minutes. This is a classic series for a reason.

Also classic is the ancient and still-excellent Diplomacy (Allen B. Callhamer), a game known for destroying friendships. Like Nevsky and Quartermaster General, Diplomacy relies on persuasion and supply. To take any territory, you’ll need a stronger force, which you’ll get by convincing your future foes to help you out with promises that you may or may not keep. Orders are written down in secret and read aloud at the table, so everyone gets to witness the stabbing of so many backs.

Diplomacy has the potential to run all day if you play till the last army bites the dust, but a few rules tweaks can help give this game new life while introducing some fun wrinkles. For example, if you score and end the game once the first player gets eliminated, everyone is suddenly invested in keeping each other (barely) alive. Negotiating to push a weaker player to the brink becomes a dangerous game, whereas it’d normally be easy to off someone in poor position. This change, among others, can cut playtime in half, making Diplomacy a much easier recommendation for larger game nights.

There’s also something to be said for a deep game with fast, accessible rules. For its scope, Diplomacy is a quick teach, and pairs well with all kinds of beverages. Just make sure you know your audience: not everyone appreciates a devastating double cross.

The Next Campaign

The Levy and Campaign system offers something new for experienced wargamers, players looking to dive into medieval conflict, or lovers of muddy roads. Nevsky is the place to start, and keep your eyes out for Žižka: Reformation and Crusade in Hussite Bohemia, 1420-1421, the upcoming new entry in the series. It may have a long title, but it also has war wagons.

Need I say more? I thought not.